Business

28 November 2021

Share

“Cartier and the Islamic Arts”, the Belle Époque of collectors

The exhibition “Cartier and the Islamic Arts” At the Musée des Arts Décoratifs reminds us that Paris was the hub of the Islamic arts trade at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Louis Cartier was part of a small circle of passionate collectors…

By Sandrine Merle.

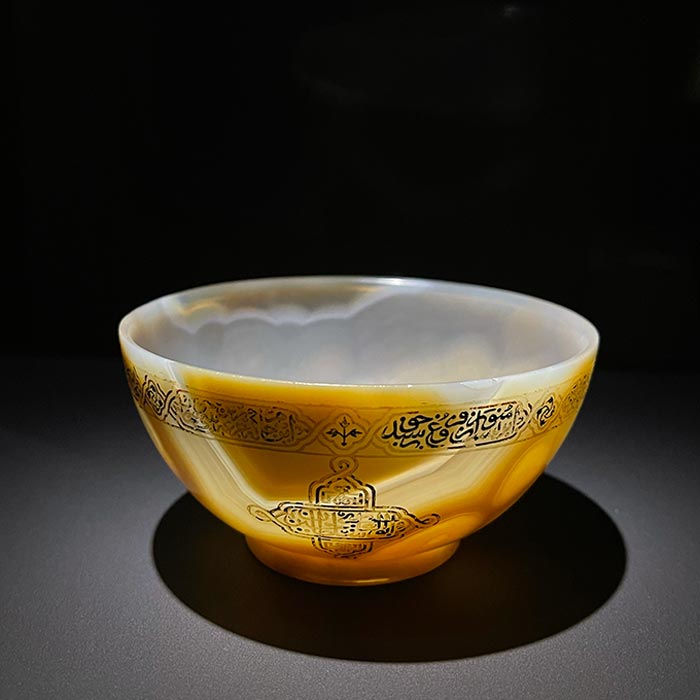

Holding “Cartier and the Islamic Arts” at the Museum was an obvious choice. The institution has long been a pioneer in the knowledge and appreciation of the arts of Islam – no fewer than 996 pieces from its collection were acquired before 1900 – not only from the Arab world, but also Spain, Iran, India and Turkey. In 1903, its “Exhibition of Muslim Arts” (curated by the great collector Gaston Migeon) presented Mamluk doors, Ayyubid brassware, earthenware tiles, kilims, and much more. According to specialists, this was the first exhibition of true scientific rigor – an echo of which we rediscover almost 120 years later in the extraordinary work of Evelyne Possémé and Judith Henon-Raynaud.

Paris, 1903

At the height of the Art Nouveau craze inspired by Japanese art, Paris had another passion: the arts of Islam. Throughout the 19th century, universal exhibitions attracted the curious with an assortment of marvels: an Arab collection dating back to the 8th century in 1867, a Mamluk collection, and the Iranian pavilion in 1878. In 1889, the reconstitution of a Cairo street on the Champ de Mars was a huge hit. The political context also favored the country’s dominant position in the trade of Islamic arts: France was in the midst of its colonial expansion. It had already conquered Algeria (1830), and also placed Tunisia (1881) and Morocco (1911) under its protectorate. It had a monopoly on archaeological excavations in Iran. And its cultural and linguistic influence exerted power in two major metropolises: Cairo and Istanbul.

Below the center of the nave of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs…

Collecting in the Belle Époque

The extraordinary economic boom brought about by the industrial revolution and trade favored the fortunes of certain families: this new bourgeoisie built up collections which they displayed in their oriental salons, and expanded to the point of transforming their homes into veritable museums. Collecting was a matter of social prestige, an affirmation of one’s status… or an entry point to the bourgeoisie! This was the case for jewelers such as Louis Cartier and Henri Vever, but also for couturiers such as Jacques Doucet: they were still considered to be simple suppliers of jewelry and clothing, craftsmen above all at the service of their clients.

6 reasons to go and see the “Cartier and the Arts of Islam” exhibition

A microcosm of enthusiasts

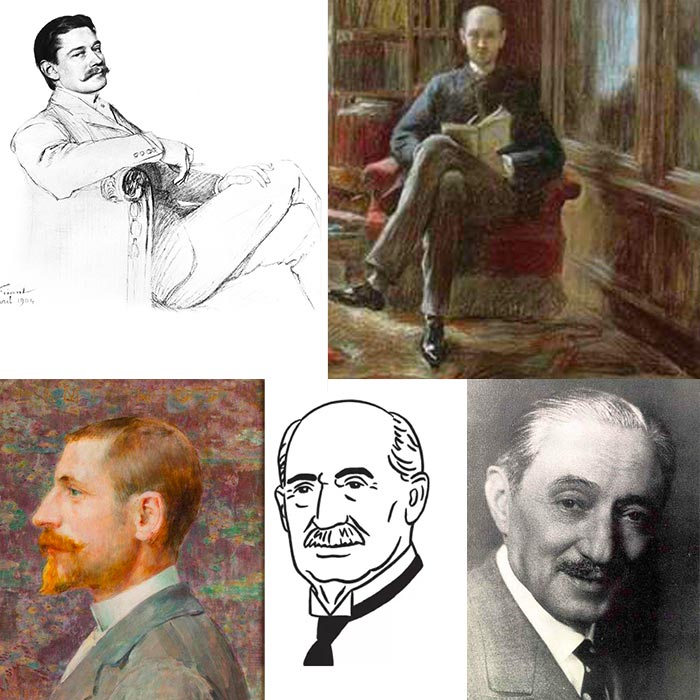

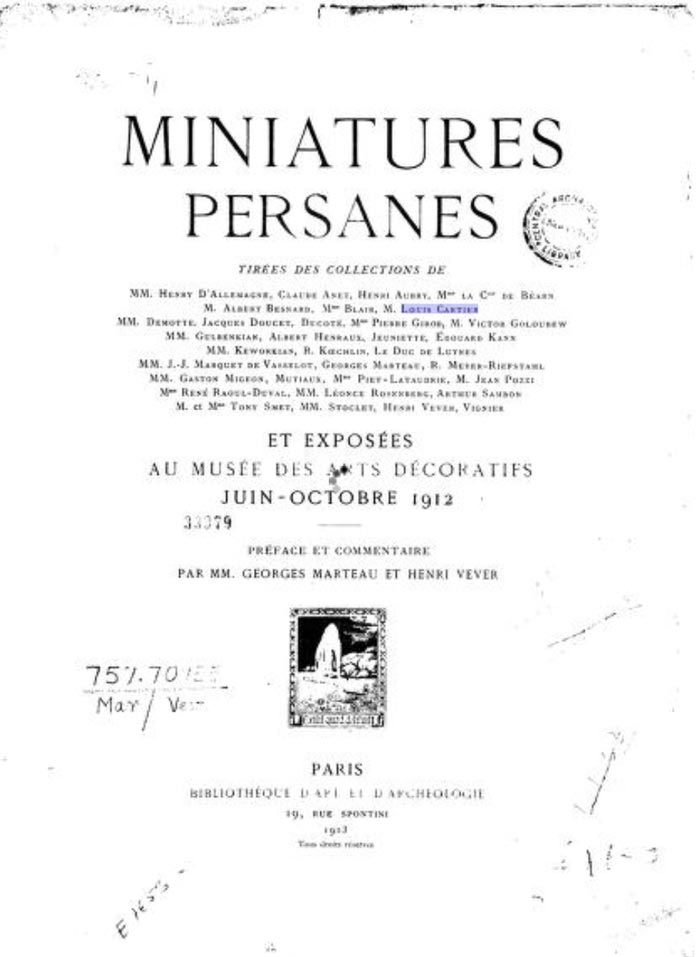

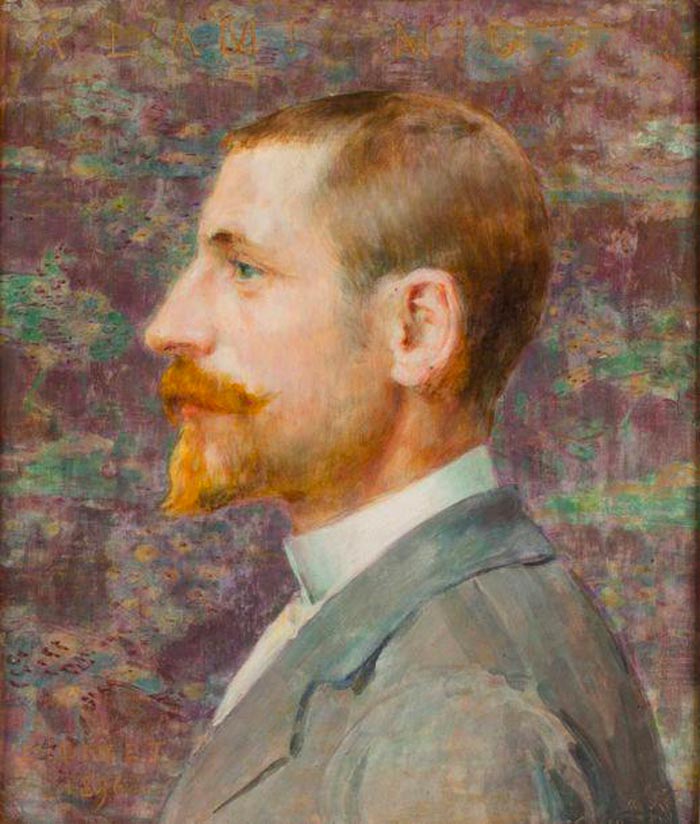

“Louis Cartier was part of a small circle of collectors that overlapped with those who were passionate about Asian art,” explains Violette Petit, director of the archives. The most emblematic of these collectors was Gaston Migeon, considered the father of the history of Islamic art, author of the first reference work, Le Manuel d’art musulman, and the initiator in 1905 of the first room devoted to Islamic art in the Louvre. He was close to Raymond Koechlin (with whom he fought in Algeria), a close friend of Jules Maciet, himself close to Georges Marteau. And it was Marteau who wrote the catalog of the 1912 exhibition devoted to the Muslim arts (also at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs) with Henri Vever… financed by Doucet. It’s a very small world! The legacy of their gifts made a huge contribution to the Museum’s collections.

The merchants

And so it was that in 1910, you were more likely to discover new treasures in Paris than in the Orient! The trade was mainly structured around large Armenian merchants who arrived in Paris as a result of the upheaval in the Ottoman Empire. Well-educated, speaking several languages, and experts on craftsmanship, they were essential middlemen, often located just a stone’s throw from Cartier. “We find almost all of them in the house’s stock ledgers,” notes Violette Petit, “Sarkissian, Malkonianz, Dikran Kelekian (located at 2 Place Vendôme), Kevorkian, the Kalebdjian brothers (at 12 Rue de la Paix)”. All the precious Persian manuscripts looted from the libraries in 1908 following the constitutional revolution, passed through their hands. In India, Jacques Cartier (Louis’s brother) obtained his supplies thanks to the close ties he established with the Maharajas and the Hungarian-born merchant Imre Schwaiger, whose offices he shared. The delight and fascination of this world of enthusiasts is reflected throughout the exhibition “Cartier and the Arts of Islam”.

“Cartier and the Arts of Islam – Aux sources de la modernité “ exhibition at the Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris until the 20 February 2022