Style

09 October 2019

Share

Questions about contemporary jewelry

Though little-known in France, contemporary jewelry already has a longstanding history.

1- Is there a precise definition of contemporary jewelry?

What is known as contemporary, avant-garde, art or conceptual jewelry is the kind designed to challenge and provoke – a kind of manifesto. “In the 1960s, Gijs Bakker made outsized jewelry in aluminum and steel, designed to thoroughly unsettle people who were too traditional, too affected. The idea was to be modern,” says specialist Benjamin Lignel. “I don’t think there’s a need to categorize jewelry as ‘contemporary’ any longer, because the younger generation are unaware of the problem, or don’t really care.”

2- Is contemporary jewelry “anti-jewelry”?

Beauty of form and valuable materials are neither its priority nor its realm: contemporary jewelry asserts the influence of art, philosophy and society issues. With ordinary metal, make-up brush hairs, yogurt pots or insects, it experiments and seeks limits, moving towards the positively disturbing, repulsive and even despicable. It consists of hand-made, one-of-a-kind pieces sold in not conventional stores but dedicated galleries like Mazlo (curatedby Céline Robin) and Elsa Vanier in Paris, Paul Derrez in Amsterdam and Funaki in Melbourne.

2- Who was the inventor of contemporary jewelry?

Many attribute its origins to Calder who was already seeking to do something different with his wire. More surprisingly, Michèle Heuzé and Karine Lacquemant point to René Lalique: “He was the first to establish a feeling more than an esthetic, as witness the Noisettes (Hazel) necklace,” says Michèle Heuzé. “He exploited the light-giving qualities of materials. Through the use of not very attractive glass excrescences representing the sky and rough enamel, this piece of jewelry expresses a personal impression: that of René Lalique setting out on a night-time walk in the country.” His friend Montesquiou even contrasted this type of jewelry with ‘stupid’ jewelry!

3- Who are the stars of contemporary jewelry?

Those who during the Sixties and Seventies (a period of questioning in every sphere) produced jewelry using ‘poor’ materials in extravagant forms and outsize volumes. Karine Lacquemant immediately cites “the Danish designer Torun, with her organic jewelry that adapted itself to the body.” In France, Henri Gargat and Gilles Jonemann were references, promoting slate, plastic, china shards and even fish scales. Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, Gijs Bakker and his wife Emmy van Leersum applied metal wire to faces and made gigantic necklaces in aluminum, presented on models in a futuristic ambiance. Ground-breaking stuff.

4- The end of the rebellion?

Carrying on from there, the Eighties abounded in manifesto jewelry. Some piece marked the period like the Otto Kunzli’s “Gold Makes You Blind” bracelet in rubber enclosing a gold ball. Over the years, contemporary jewelry has developed and matured. Today it can no longer be reduced to simplifying demonstrations and outmoded provocations. It now faces the same problems as contemporary art: it has an end in itself. It now has its own history, one unperceived and unknown, which now needs to be written. And this is what Monica Brugger, a key figure in contemporary jewelry (which she teaches in Limoges), is about to tackle.

5- Which names should we be aware of today?

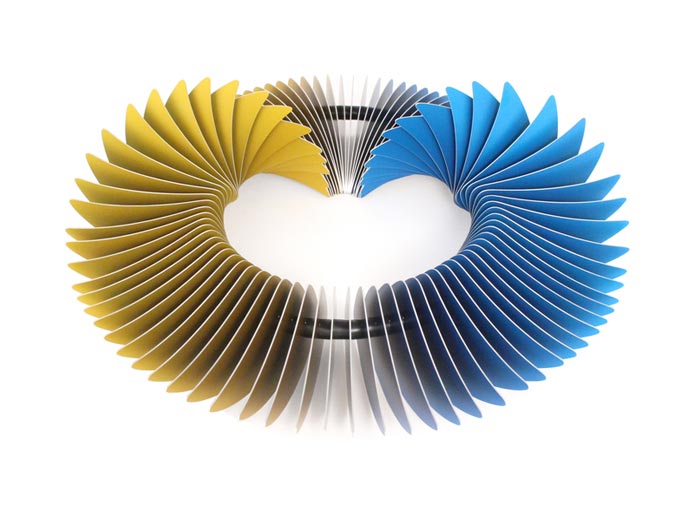

There have never been so many! First of all, we have a leading light in the shape of Swiss designer Sophie Hanargath whose leitmotivs are humor, desire, the body and surrealism. One of her most iconic pieces is the scarf-necklace featuring testicles which falls to groin level. Then there is Noon Passama, with her half-human half-animal heads in fur, and her work based on the chain; Isabelle Busnel with jewelry (cameo brooches, pearl necklaces, etc.) revisited in white silicone; Vietnamese designer Sam Tho Duong, who recycles yogurt pots in gigantic necklaces evoking late Renaissance ruffs, and Mariko Kusomoto with her translucent jewelry combining textiles with a Japanese folding technique.

6 – What about French designers?

France is certainly not the type of breeding ground found in North European countries, Australia and New Zealand. “Here you find a long list of ‘sins’ condemning this type of jewelry,” says Elsa Vanier. “France, the cradle of haute joaillerie, does not consider it precious enough, but too extravagant, too unwearable, rather. Meanwhile, the art world only registers the word ‘jewelry’ and the fact that it is designed to be worn.” With its allegiance to luxury brands, France has hitherto given it little credence. Luckily there are events like the Jewelry Weeks in Munich, Barcelona and Athens. “And thanks to the Internet and social media, curious spirits at last have an opportunity to talk about it,” says Céline Robin. Visible as never before, contemporary jewelry has now embarked on a new chapter in its history.

Banner image : Mariko Kusomoto

Related articles: