Business

24 March 2020

Share

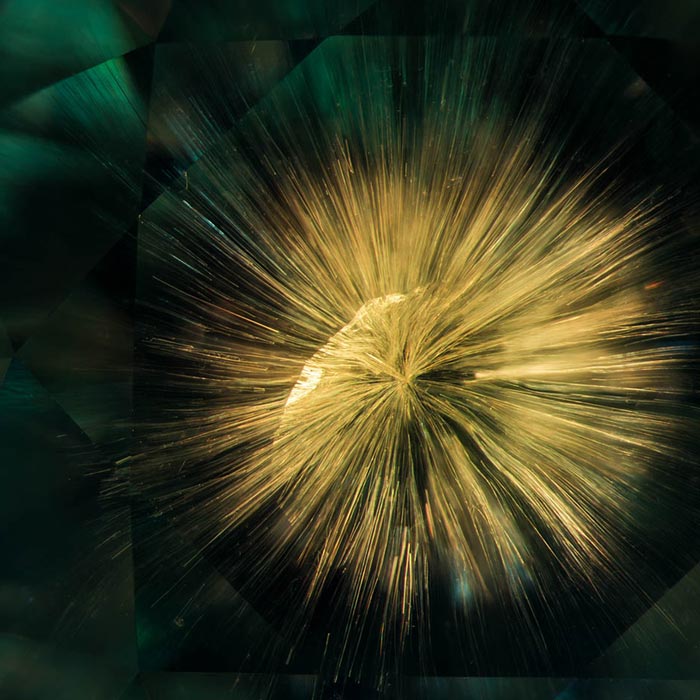

“Inside Out: Journey into the center of a gem” with Billie Hughes

During an Evening Conversation at The School of Jewelry Arts, Olivier Segura* interviewed gemologist Billie Hughes. Through her fascinating photomicrographs, she reveals to us the inner world of gemstones.

By Sandrine Merle

Pictures : Lotus Gemology

Banner video : Moving CO2 bubbles in a pink sapphire – Wimon Manorotkul/ Lotus Gemology

Olivier Segura. How did you become a gemologist?

Billie Hughes. My parents, themselves gemologists, used to take me with them to the markets, mines and stone deposits in all four corners of the globe. Despite these early beginnings, I never thought I would follow in their footsteps. I chose to study political science at UCLA. But my parents encouraged me to do a course in gemology all the same… And from the moment I started to see the stones from the inside, I was completely hooked!

O.S. What does your job consist of?

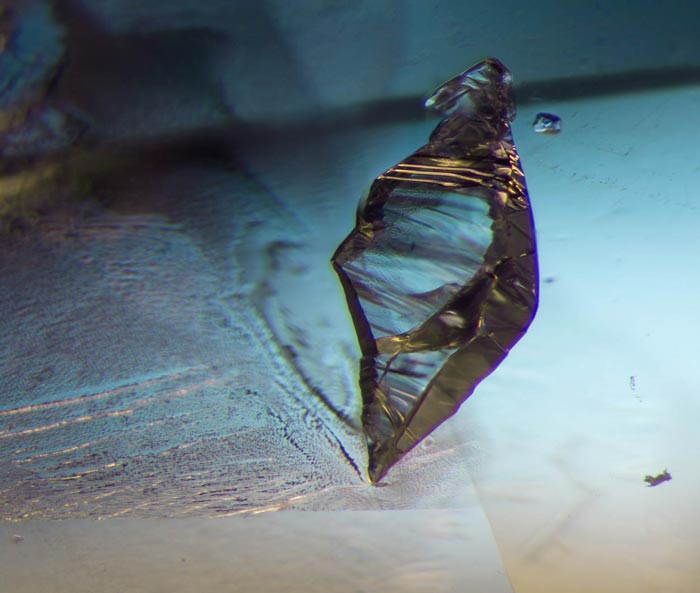

Billie Hughes. My job is to put together the gemological report, which is like an ID card. Five years ago, I co-founded the Lotus Gemology Laboratory, located in Bangkok, the world center of the colored gem trade. We specialize in rubies, sapphires and spinels, but we do not test diamonds. If the stone is blue, it is up to us to determine whether it is a sapphire, aquamarine or topaz. If it is red, is it a ruby, a garnet or a banal colored glass? Is it natural or has it been modified by human hand? To find clues, the only solution is to go inside! There are traces of potassium, gallium or vanadium. There are also inclusions, solid, liquid or gaseous irregularities.

O.S. How do you undertake this journey into the heart of a stone? Is it enough to use a magnifying glass or do you need other instruments?

Billie Hughes. The most important tools for a gemologist are not necessarily the most expensive. As a young graduate, I asked my parents how to tell one ruby from Mozambique from another, from Burma, because there are many similarities between the two stones. Their answer was “after 30 years of experience, you know.” It wasn’t necessarily what I was expecting but they were right, the primary tool is the eye. Then comes the magnifying glass and of course the microscope.

O.S. You make photomicrographs that have won many awards and have been published in specialized journals or the Wall Street Journal. How did you get started?

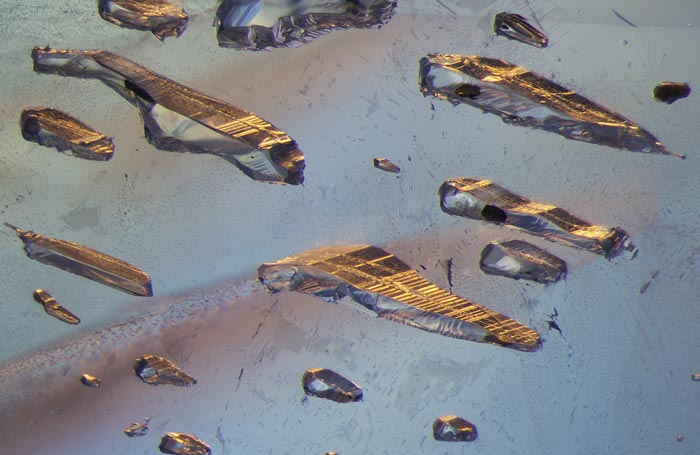

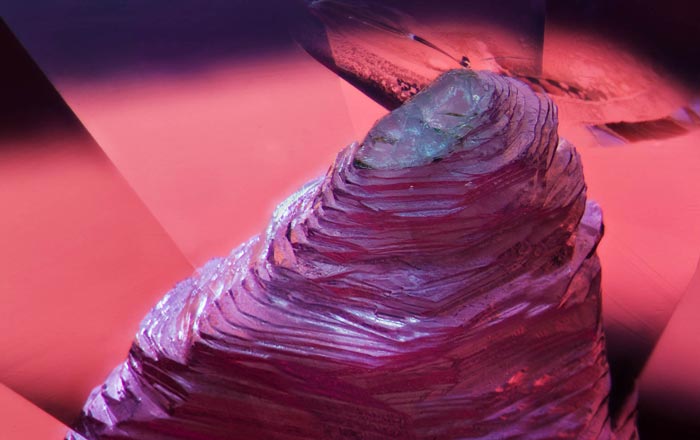

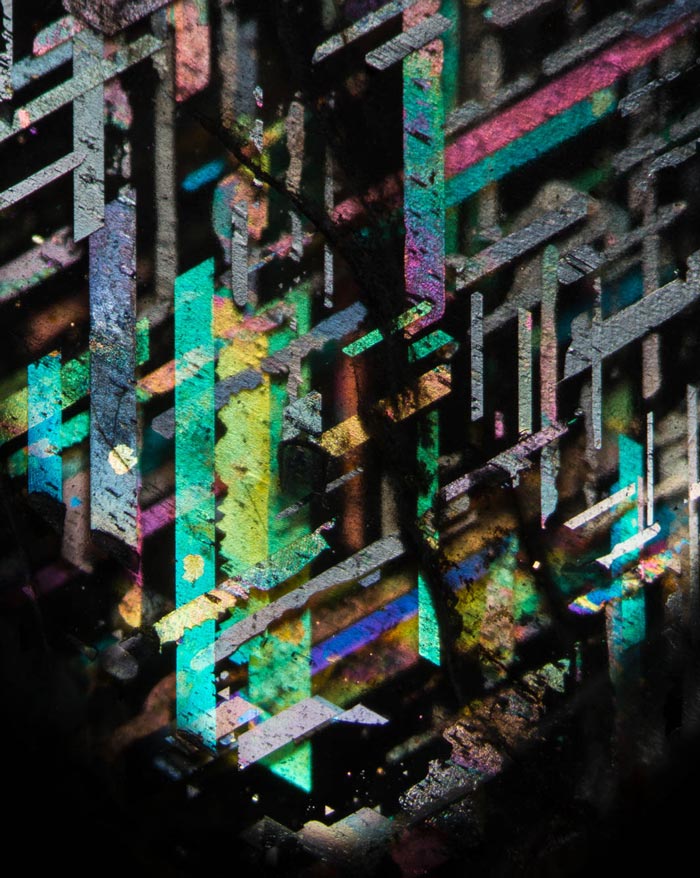

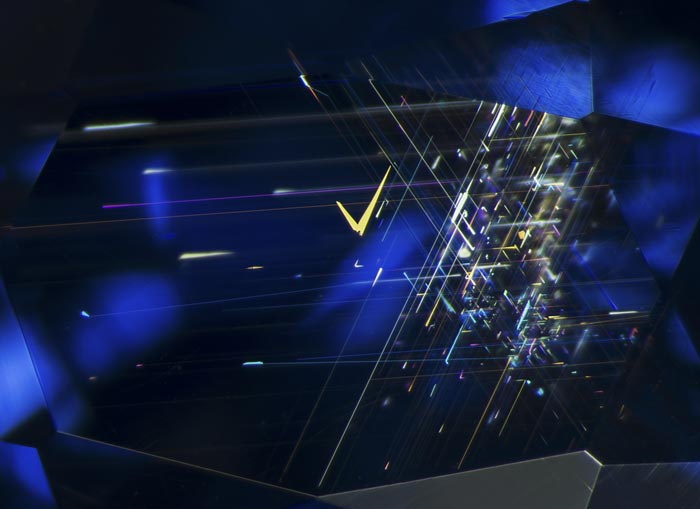

Billie Hughes. Entering the inner world of these crystals is a bit like diving: there’s so much life and movement in there! Instead of finding chaos, I discovered a very orderly and structured universe. Sometimes you see real spectacles as in this Sri Lankan sapphire traversed by black graphite crystals encapsulated in negative crystals. It’s magnificent, it’s like space shuttles in the Star Wars movie. In this pink sapphire, gas bubbles go here and there. There are also abstract paintings formed by needles positioned in multiple directions, as in this garnet from Australia or the one from Russia.

O.S. For those who would like to see more, are there any photographs available on the Lotus Gemology site?

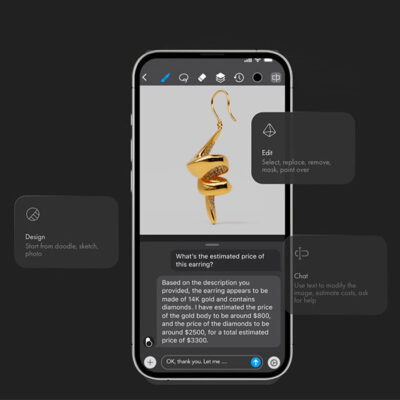

Billie Hughes. As I began analyzing stones with a microscope, I started to take photos of these wonderful images and make accurate descriptions. I then set out to share them with gemologists and the general public through Hyperion, a search engine integrated into our website.

O.S. Are these inclusions considered as beauties of nature or defects in a commercial transaction?

Billie Hughes. Inclusions are often seen as defects, but this is not always the case. For example, I had a ruby filled with very bright red staurolite crystals. I had never seen that before, it was extraordinary! Stone owners are usually not very interested in inclusions, but this owner understood that they were an added value: he wanted to have the picture published in the auction catalogue next to the one of his ruby. As far as I’m concerned, I get bored when there’s nothing happening inside a stone!

O.S. Is it also possible to determine the geographical origin, which is a key factor in the value?

Billie Hughes. Yes, so much so that a client asked me if there was an “origin machine”, that is, a machine that would make it possible, simply by placing a stone in it, to determine its origin. The answer was no. The gemologist is like a doctor assessing a medical condition: he has to perform tests and in this case a microscope is not enough. Ultraviolet light, spectrometry or chemical analysis must be used. And two gemologists studying the same stone can come up with two quite different diagnoses.

O.S. There’s a very interesting case of Mozambique rubies versus Mogok rubies in Burma.

Billie Hughes. As I said it’s sometimes difficult to determine if a ruby comes from one or the other of these places because they are similar. Our clients don’t always understand this because the deposits are thousands of miles apart. Our role is to explain to them that they were formed in the same place 50 million years ago but then the tectonic plates moved: the Indian subcontinent collided with the Eurasian plate creating the world’s highest mountain range, the Himalayas. Having said that, I believe that provenance is not the be-all and end-all. Just like in painting: the imperfect work of an unknown can be sublime and touch you unlike that of another, very famous artist.

O.S. You say that gemology is the perfect conjunction of art and science.

Billie Hughes. Today the greatest value is placed on natural stones, those that have been least modified by man. It’s hardly surprising, because it’s an extraordinary experience to hold in your hands stones formed hundreds of millions of years ago. They were there long before us and will be there long after us, which is true of very few objects that we can afford. They speak of the history of the cosmos and the origins of life. Observing them gives rise to a great many metaphysical and spiritual questions.

*Olivier Segura, scientific director at The School of Jewelry Arts

Related articles: