My agenda

09 November 2024

Share

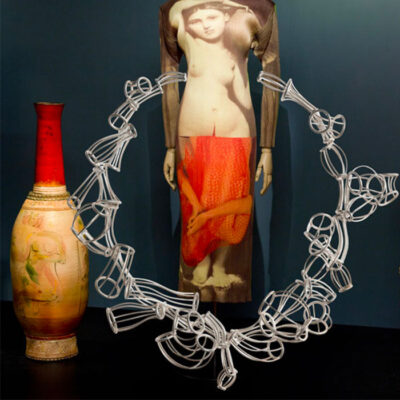

Immerse yourself in the book “Diamonds of Golconda” by Capucine Juncker

Surprising as it may seem, this is the first book entirely dedicated to diamonds of Golconda ; until now, they have only appeared in general works. An interview with Capucine Juncker, the author I met 10 years ago on a trip to Golconde.

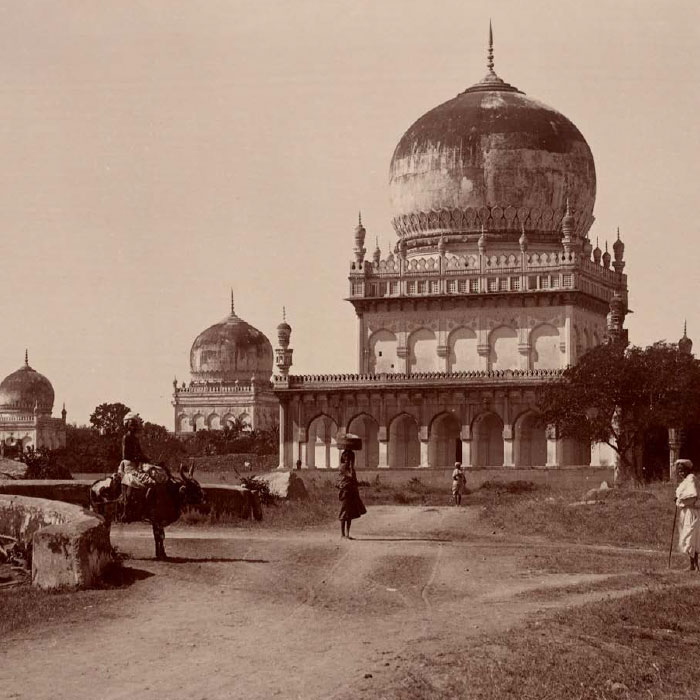

Sandrine Merle. The title “Diamonds of Golconda” implies a region, not the city where the famous fort is located.

Capucine Juncker. Golconde was first a fort, then a capital and, by extension, the name of one of the five sultanates of the Deccan. These mythical diamonds were mined between antiquity and the 18th century, in alluvial mines located throughout the Deccan region. They were spread over vast stretches of land between the Godavari, Krishna and Penner rivers, and are nowhere near complete. Golconde was the main trading center.

S.-M. What were your sources?

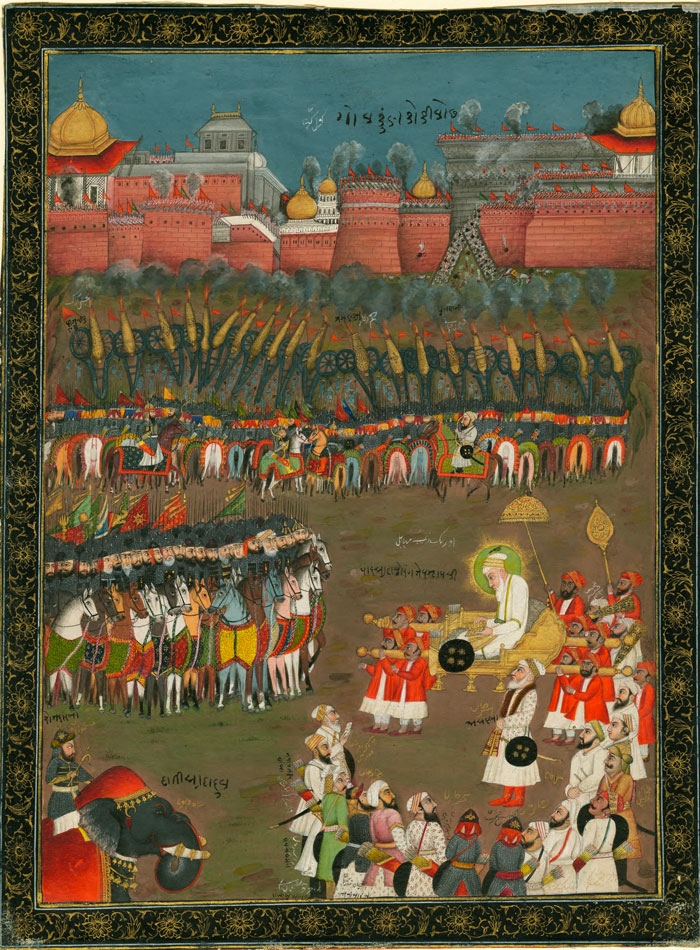

Capucine Juncker. I mainly studied French sources, which are particularly rich. We often talk about the writings of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, Louis XIV’s official merchant, but he wasn’t the first to describe the Golconda mines, contrary to what he would have us believe. As early as 1580, the Mughal emperor Akbar brought Jesuits to his court. This tradition of receiving Europeans (priests, teachers and doctors…) continued with his successors Jagangir and Shah Jahan. I also spent a lot of time looking for jeweled diamonds on Mughal miniatures, but before Jahangir, they only appeared on works of art: regalia, flycatchers, penholders and footstools.

S.-M. In these mines, some of the most beautiful and extraordinary specimens have been discovered?

Capucine Juncker.

Golconde was the only mine to produce Type IIa diamonds (until 1725, when they were also discovered in Brazil), i.e. the purest chemical type with exceptional optical transparency. But above all, they convey the richest imagination. The Orlov, the Sancy, the Hope, the Eye of the Idol, the Hydrangea… the most exceptional have been named. Their history is known thanks to the names of the owners, often great historical figures who have succeeded each otheŕ since the 18th century. Some of them have had incredible destinies. Let’s take just one example, the Régent, the largest and most exceptional in my opinion: discovered by a slave at the end of the 17th century, it was stolen, hidden, and bought by the Louvre museum.

S.-M. In this book, you set out to show how these wonders came to us.

Capucine Juncker. The Mughals, nomadic warriors from Central Asia, traditionally had a taste for spinels. When they landed in India in 1526, they began by appreciating pearls, but they also came to cherish Colombian emeralds, which were the color of Islam; they engraved them with calligraphic verses and floral decorations. And they also learned to love diamonds, the fetish stone of the Hindus since Antiquity. It became the symbol of royal power, and very few left the country. A turning point came when Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1876: these stones began to circulate in greater numbers in European courts. Then the trade, via auction houses, took hold of these stones, which then passed into the hands of wealthy American heiresses and jewellers such as Tiffany & Co., Harry Winston, etc. If diamonds had not been associated with power, Europeans would probably not have been so interested in them.

“Diamonds of Golconda”, Skira Paris, 2024

Related articles: