Style

19 November 2019

Share

(Re)discovering Lacloche Jewelers

The School of Jewelry Arts is devoting an exhibition to Lacloche Jewelers, with an accompanying monograph. It is a well-deserved tribute for a French jewelry house that enjoyed iconic status before sinking into oblivion in the late 1960s.

The exhibition is curated by Laurence Mouillefarine, who also co-authored the book “Lacloche Jewelers” with Véronique Ristelhueber. As the invited guest at the last School of Jewelry Arts “Evening Conversation”, hosted by gemologist and journalist Capucine Juncker, Laurence outlined the Lacloche saga and shared entertaining highlights from her quest for jewels and archive material.

“Lacloche Jewelers”: the idea for the book

Francis Lacloche, the grandson of one of four brothers who founded the eponymous house in 1892, came up with the idea for the book. The brothers were Belgian, of Jewish extraction. Laurence recounts: “Their father was a peddler who died very young. Probably their father-in-law, a goldsmith and jeweler, was the one who got them interested in the jewelry trade.” The oldest two brothers, Léopold and Jules, set up shop in Rue de Châteaudun in Paris, while the younger two, Jacques and Fernand, worked in Madrid. One brother died in a train accident between Biarritz and Paris, and in 1901 the others consolidated their businesses into one, which enjoyed stellar success. They got new premises at 15 Rue de la Paix and then a shop in London’s very fashionable New Bond Street. Lacloche Jewelers were always just a few doors away from Cartier and shared the same clientele. Some of the world’s most illustrious gemstones passed through their hands. For the new Duchess of Westminster they made a tiara mounted with two pear-shaped Golconda diamonds (weighing 23 and 33 carats) given to Queen Charlotte of England by the Nawab of Arcot. Lacloche Frères opened boutiques in Biarritz, San Sebastian, Cannes, and Nice. They made extremely good marriages – delighting their ambitious mother – and this may have facilitated their meteoric rise.

The 1925 International Exhibition – a key milestone

Lacloche distinguished itself at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, held in Paris, France – the world capital of fine jewelry-making – where, as Capucine Juncker makes clear, “The chief criterion was to show pieces that bore no reference to the past.” In a gilded marquee at the Grand Palais thronged with elite jewelers like Van Cleef & Arpels, Cartier, and Sandoz, their Fables de la Fontaine-inspired jewelry was an instant hit with the press. People went wild over “The Fox and the Crow” pendant, with its superb yellow diamond “cheese”. Lacloche also drew a lot of attention for the exquisite boxes that were their specialty: powder compacts, vanity cases, and cigarette cases for liberated women who now smoked and touched up their makeup in public. The other rule at the World’s Fair was to mention the names of their workshops: Lacloche Jewelers used Lenfant, Verger and Pery (among the best in Paris), and as Laurence says, “They absolutely deserve to have a section of the book devoted to them”.

Characteristically Lacloche

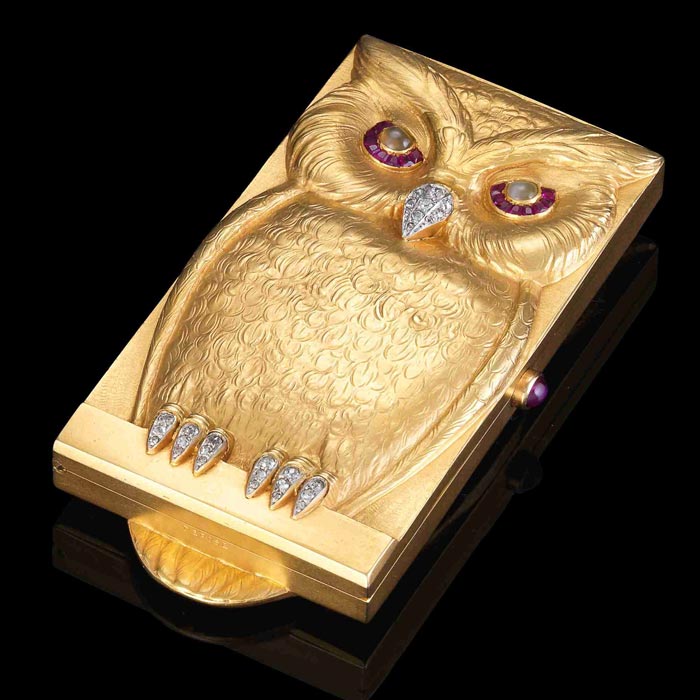

None of the jewelry houses employed in-house designers at that time. Like Van Cleef & Arpels or Boucheron, the Lacloche brothers would pick and choose among the pieces that their workshops came up with. Hence some very similar designs, like diamond bracelets with Egyptian-style patterns, are found among several of the big jewelers. Laurence observes that “it’s difficult to define a specific Lacloche style, but one thing is certain – their designs were tasteful, original and often quite bold”. See for instance their owl box, the bat bag (a lesbian symbol in those days), or most obviously the stunning rock crystal pendant watch with a sculpted nymph, covered with faceted amethysts. This is a jewelry masterpiece, as is the bracelet of platinum “lace” and diamonds with “petit point” tapestry. It was inspired by a technique used by Fabergé (whose stock Lacloche London acquired in 1917) that can be seen on an Easter egg gifted to the Russian Tsar. Apparently one of his designers got the idea from seeing her mother-in-law embroidering a tapestry.

Dedication to detail

“This petit point bracelet exemplifies Lacloche’s painstaking attention to detail,” enthuses Capucine Juncker. “Every hole was drilled by hand, which is unimaginable today.” The cases also showcase the art of gem carving, showing a lifelike sprig of cherry blossom unfolding over a lid against an empty background. Equally breathtaking is a bracelet made of 283 baguette-cut diamonds, whose subtle brilliance undulates beneath the light. When you know how wasteful the baguette cut is, this bracelet seems all the more precious. The catalogue cover features a 1925 bracelet that is just as remarkable, with an articulated mounting, millegrainsetting with small stones, and polished cabochon ruby petals.

Lacloche rises from the ashes

Despite its renown, the company went bankrupt in 1931. Not because of the 1929 crash, or bad management, but because one of the sons was an incorrigible gambler. Everything had to be sold – the premises, the stock, and the order books. Five years later another son, Jacques Lacloche Jr (father of Francis), relaunched the company in his own name with shops on Place Vendôme and La Croisette in Cannes. His penchant for modern art was evident in fully articulated pieces, and a bracelet with removable cabochons of coral, turquoise or sapphire. Success came swiftly, with clients including Prince Rainier of Monaco, Elsa Schiaparelli and the Prince of Nepal. Lacloche preempted Cartier as the first jeweler to launch a fragrance, N°1. Then in 1967, he left jewelry behind to open a design gallery on Rue de Grenelle. “He became so well known for his gallery that we’ve forgotten his jewelry,” laments Laurence. “He was behind Roger Tallon’s spiral staircase!”

Remarkable detective work

Jacques’ son Francis Lacloche managed to save the stock ledgers from being destroyed, so this period of Lacloche’s history is relatively well known. However, for the earlier years from 1892 to 1931, “the only clue we could find – after 6 months of research – was a little catalogue published by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs commemorating the 1925 exhibition. And even that carried no pictures, just a few lines saying ‘Lacloche Frères – Album of 63 watercolors – Jewels and cases, Lacloche Frères – Album of 21 small clocks, original watercolors’”. Some fine sleuthwork led Laurence to discover that these albums had been rescued, auctioned off by Jacques Lacloche in the late ‘70s, bought by a Geneva dealer, then sold on to a New York collector… who had just died when she called him! She finally caught up with them at the house of their new owner – another New York dealer, and a drawing aficionado. So after over two years of research, these two wonderful albums enabled the authors to write their monograph and put together the exhibition, which features 76 pieces of jewelry from all around the world. Definitely well worth seeing.

Shop the “Lacloche Jewelers” monograph co-published by the Editions Norma and the School of Jewelry Arts

“Lacloche Jewelers” exhibition until 20 December 2019 at The School of Jewelry Arts

Related articles: