Style

17 July 2021

Share

Nardi, the Moor of Venice

In Venice, I met Alberto Nardi, a third-generation representative of the Venetian jeweler well-known for its Moorish heads. A type of jewelry he champions, despite the controversies aroused by cancel culture in English-speaking countries.

By Sandrine Merle.

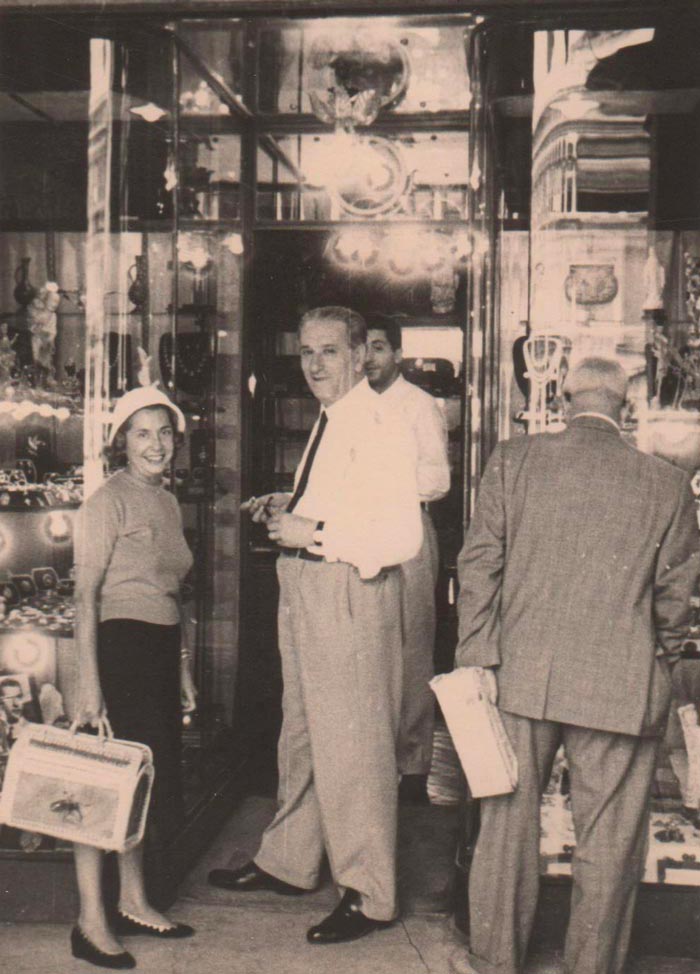

Alberto Nardi received me in St Mark’s Square, in the historic store set up by his grandfather Giulio in 1920 not far from the Doge’s Palace and the celebrated basilica. He took over the business from his own father. The Nardi family has close ties with the city, which Alberto knows inside out. “I have intense feelings for it – half love, half hate”, he says. The positive side includes its extraordinary history, unique beauty and impressive architecture, including this basilica, where he had the extraordinary privilege of getting married. But there is also the endless stream of tourists and the ever-more frequent and frightening high tides. One of them destroyed almost all the archives in the 1960s. Taking up the fight, he worked with the mayor before becoming vice-president of Save Venice, an American association that has safeguarded and restored a host of masterpieces: mosaics, sculptures, ceilings and paintings by Carpaccio, Titian and others.

Jewelry paying homage to Venice

Among Alberto Nardi’s jewelry, the Veneziani clearly celebrate the Serenissima, with a ring depicting the Rialto Bridge, earrings shaped like the Basilica della Salute and enamel masks evoking the famous masked balls. But his emblematic piece remains the Moretto, an ebony-faced prince in a gold robe and turban richly decorated with stones. He is Shakespeare’s Othello in “The Moor of Venice”, or Balthazar, one of the Magi, who brought the gift of gold. “My grandfather did not invent the moretto; he revived it in the 1940s with a model made for Queen Paola of Belgium. The moretto’s origins lie in Dalmatia, which once belonged to the Venetian Republic. As a symbol of the exchanges between East and West, it was highly fashionable in the 18th century, when Orientalism was all the rage,” says Alberto. One of the finest models, Tree of Life with its openwork bust in gold and diamonds, was created by Giulio Nardi in 1947 for his wife Giuseppina, and is still produced. “They reached their peak in the Fifties and Sixties,” says Nardi – promoted by outstanding ambassadors like Elizabeth Taylor and Grace Kelly. To date, over 7,000 pieces have come out of his Venice workshops, mainly one-of-a-kind pieces with garments sporting turquoise cabochons, or trimmed with briolette-cut stones. One even opens onto a view of Venice in relief. The stone-encrusted turbans feature crosses, aigrettes and crescent moons.

Challenging times

Then in 2018 came a thunderclap. At her first Christmas at Buckingham Palace, Meghan Markle considered Princess Michael of Kent racist for wearing a Nardi blackamoor brooch. “I immediately received messages of support from all over the world. I was saddened and angry that I could be put on trial like this, and that a part of the world lacking in culture could impose its own vision,” says Alberto Nardi. These militants have the wrong target: can a slave be represented like this, decked out in precious materials? The face does not have a specific definition, in fact: it chiefly represents the foreigner, the Oriental and the African. In short, it’s an extremely imprecise category that has varied considerably over time. Nardi, whose clientele is largely American, has nonetheless decided to do away with this ethnic aspect, and now sculpts faces with Western features in colored stones like turquoise, amber, lapis lazuli and coral. “I want to focus on aesthetics rather than politics by evoking Turkish-style work.”

This keen admirer of Marco Polo has thus risen brilliantly to the challenge, though another awaits him: to safeguard this independent company in a context of all-consuming globalization. But that’s another story.