My agenda

16 April 2023

Share

Discover contemporary jewelry in the exhibition “Hair and Hairs”

The exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris) presents hair jewelry, both ancient and contemporary. How are artists and designers today revisiting this lost craftsmanship at the beginning of the 20th century?

By Sandrine Merle.

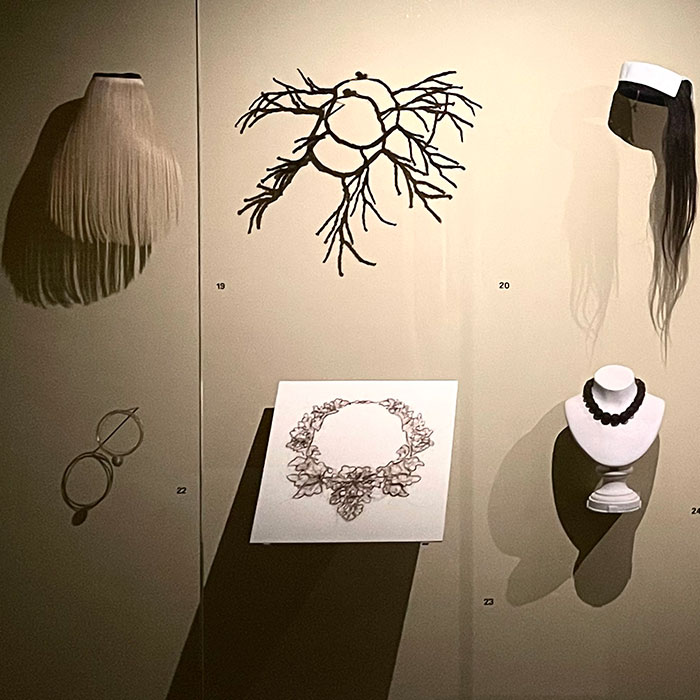

Exhibition curator Denis Bruna has reserved a room for braided hair jewelry, as well as creations worked in mesh, intertwined in a ring, and so on. Jewelry that mimicked passementerie in this way enjoyed its peak in the 19th century, when it was used to testify to devotion between lovers, to commemorate a precious moment, or to signify the mourning of a loved one. The virtually indestructible bodily material conjures up ideas of immortality: one can still see Marie-Antoinette’s hair trapped in a ring (at the Carnavalet Museum). And yet whether alive or dead, hair often provokes disgust and rejection. “Surprisingly, it fascinates many young artists and designers,” notes Denis Bruna. As Ana Escobar explains so well in the catalogue, “They explore and interpret this material by tackling subjects such as identity, memory, gender, politics, and social taboos.” Here are five designers who are featured.

Kerry Howlay

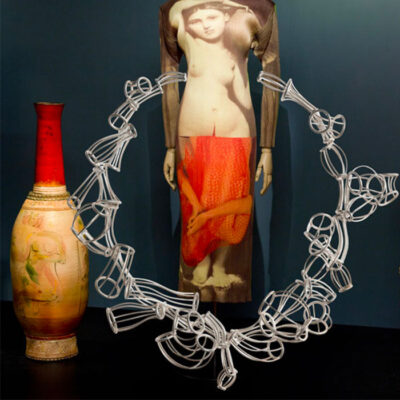

The English artist spent 60 hours weaving hair collected from friends. Her slightly frothy necklace “Attraction and Aversion” is perfectly named; it evokes delicate silk lace made in the 18th century but also a tangled hairbrush or a tuft stuck in the bathtub drain.

Mona Hatoum

This multimedia artist – born in Beirut to Palestinian parents – collects hair, fur, and nails. Her surreal and unsettling necklace initially evokes a pearl necklace, but it is actually made of hairballs. It echoes the 19th-century mesh necklace displayed in the nearby showcase. Hatoum also memorably used women’s hair for a keffieh exhibited at the Pompidou Centre in 2015.

Sonya Clark

This tentacular crown necklace made of kinky hair raises questions about discrimination, racial identity, and cultural biases. “I have been working with this material for 25 years: it says a great deal about us and our ancestors,” explains Sonya Clark. In Africa, the way it’s styled helps signify ethnicity, social status, wealth, or religion. For this reason, slave owners sought to erase this form of identity by shaving their slaves’ heads.

Mélanie Bilenker

No problem if you have an aversion to hair: in this case the material is hardly recognizable! The American jewelry artist merges the Victorian-era miniature portrait (the pinnacle of hair jewelry) and contemporary photography: she goes about her daily activities (eating chocolate, writing or having breakfast) in front of the camera. She then “pencils” these scenes using hair fragments glued one by one onto a paper background.

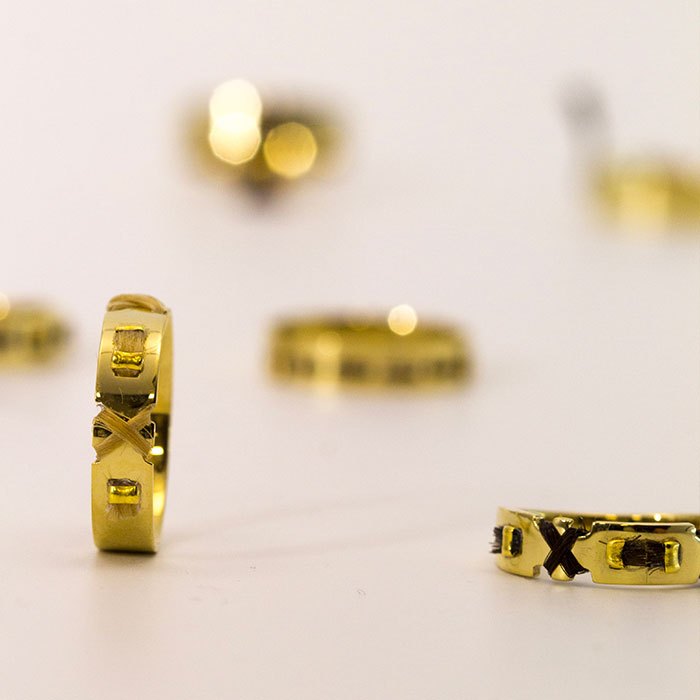

Erwan Palaric

Three pieces of jewelry by this jewelry artist, the youngest amongst them, are featured in the exhibition. He revisits the 19th-century passementerie effect, particularly with wedding rings made with strands of lovers’ hair that resemble ribbons intertwined in brass. On the gold plate ring, the strands of his recently deceased parents poetically mingle in a cross-stitch that revisits the works of the 19th century.

Marisol Suarez

When she worked at Tony&Guy, Marisol Suarez would leave with bags full of hair that she would braid, burn, glue, and so on. Experiments that led her to create real works of art, like this piece on display: the extraordinary headdress formed by braids, a nod to the poufs of the 18th century. Much more suited to everyday wear, her hair combs designed to discipline the hair form a sublime mise en abyme. Enough to rehabilitate this material in jewelry once and for all.

Related articles:

The historical part of the gallery des Bijoux in the Musée des Arts décoratifs