Business

12 June 2023

Share

Jewelry workshops, the new gold mines

Bouder, Verger Frères, Lenfant, Abysse, Bermudes, SBA, Cristofol, Mathon – names that probably mean nothing to you, but are among the thousands of jewelry workshops that, since the beginning of the 20th century, have been manufacturing jewelry for renowned houses. After a series of difficult years, they are now the object of everyone’s desires as the jewelry market is booming.

By Sandrine Merle.

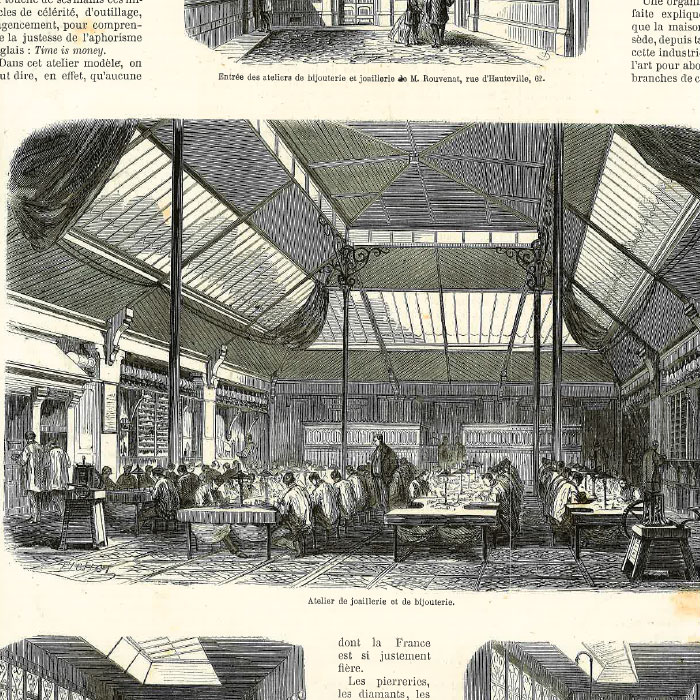

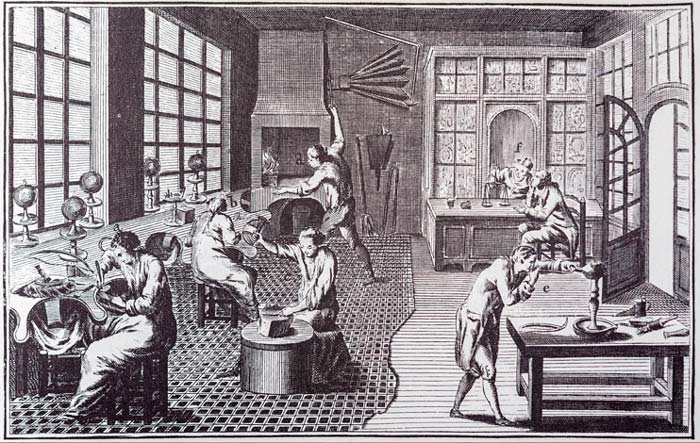

These workshops, often located in Paris, set up in backyards or on upper floors, have created some of the most beautiful pieces in the history of jewelry, such as Van Cleef & Arpels’ mysterious-set clips, Lacloche’s Art Deco bracelets, and Cartier’s “Tutti Frutti”. Originally, they were highly specialized family structures, consisting of less than 10 workers crammed into somewhat unsanitary rooms. Working separately in gold beating, stone cutting, goldsmithing, polishing, and more, these workshops operated as a network. Throughout the 19th century, many of them were transformed into larger-scale factories with increasing mechanization and industrialization following Taylorism. These were no longer small attic workshops but still far from the thousands of square meters dominated by machines of today, some of which are capable of setting a diamond in a single second.

The mysterious disappearance of Rouvenat

French workshops in high demand!

Today, regardless of their size, these French workshops face tremendous demand for their jewelry, boosted by the fine jewelry segment, a mass-production sector somewhere between affordable and high-end jewelry. The global market size was estimated at USD 256 billion in 2021 and is projected to exceed USD 517.27 billion by 2030 (Facts & Factors). Furthermore, after COVID, the workshops are obliged to absorb the relocation of that part of the production that was done in Asia. Overwhelmed and under pressure, they can no longer keep up and have become the target of acquisitions by their clients, who are constantly seeking greater production capacity. LVMH has just made a significant move by acquiring 5 workshops (including Orest and Abysse, two leading European companies in the sector) through a majority stake in the Platinum Invest group. A smart move with the aim of securing production for Tiffany&CO., which “will exceed one billion dollars in operating income for the first time” (Bernard Arnault).

Integration across the board

Another solution to increase production capacity is for clients to create their own factories, as Bulgari and Van Cleef & Arpels have done. Van Cleef & Arpels will soon open two factories, each employing 300 people, one in Drôme and the other in Auvergne, thus contributing to the reindustrialization of France. “This verticalization of production allows for supply chain control and improves the traceability of both jewelry and gemstones,” explains Bénédicte Epinay, General Delegate/CEO of the Comité Colbert. This is the logical extension of the integration already achieved downstream: multi-brand boutiques have given way to proprietary stores. The brands have full control from A to Z.

Survival of the biggest

In this context, smaller clients are relegated to the background. “The delivery of the last collection was a nightmare, which ultimately led me to acquire a workshop, a prerequisite for brand development. It was such a tortuous process to find them that I can’t even reveal their name,” jokes Véronique Tournet, founder of La Brune et La Blonde. Rachel Marouani, founder of Talisman by. has adopted the same strategy by finding a workshop of 12 people capable of making chains, stamping, and grand feu enamel. “Talisman by. is based on the ‘Made in France’ concept and customization, so I had to ensure my independence in order to be able to meet the promised deadlines to clients, regardless of the circumstances. If we optimize the processes, the workshop will also be able to supply other brands.” This domino effect will force very small businesses to manufacture their jewelry abroad, in Portugal or even in Asia; Italian workshops are facing a similar situation.

Training – a sine qua non

Already under pressure, manufacturers also have to confront a shortage of labor due to the lack of generational renewal. According to Jacqueline Viruega in her book “La Bijouterie Parisienne 1860-1914,” this problem dates back to the end of World War II with the disappearance of chisellers, piercers, and polishers. “The situation is such that young jewelers are demanding high salaries and are becoming increasingly demanding about working conditions,” notes Armelle de Blanchard, a consultant in the sector. However, they are increasingly refusing repetitive work more akin to an operator’s role.” To address this shortage, which schools are also struggling to meet, brands like Richemont and LVMH are setting up shop near schools, organizing or participating in events targeting younger generations (such as “De Mains en Mains” by Van Cleef & Arpels or “Station F” by the Comité Colbert), and creating their own training centers. The market is exploding to such an extent that their workshop directors are leaving to create their own schools as well. Similar to Jérémy Boueilh (ex-Cartier among others), who offers accelerated training in gem-setting. An incredible upheaval is underway.

Related articles:

TFJP x Comité Colbert, the savoir-faire and gold métiers of gold jewelry