Business

02 November 2022

Share

5 things you need to know about the impact of gold mining on nature

L’or du Monde, one of the pioneering jewelers in the use of recycled gold, invited me to a lecture given by Aurore Stéphant, expert mining geologist and co-founder of the association Systext. An apocalyptic account of the ecological impact of gold mining.

By Sandrine Merle.

1/ The typical gold mine

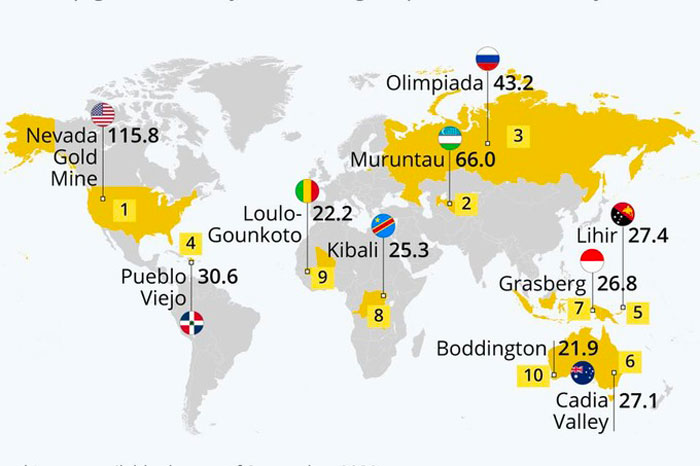

A gold mine is never entirely dedicated to gold: it always extracts other minerals. It’s an open-pit and primary mine – in other words, it requires blasting the rock. It’s also an industrial undertaking: 80% of the world’s production comes from huge operations, the rest from small mines, both legal and illegal. Contrary to popular belief, the typical mine is not necessarily in Africa. South Africa had been the leading gold producer for 102 consecutive years, but in 2007 it was overtaken by China. The latter now produces between 300 and 350 tons of gold per year, i.e. 10% of world production. And no country has a monopoly: gold can be found in Russia, Australia, Canada and the United States. One of the two largest deposits in the world is in Nevada.

2/ Extraction is speeding up

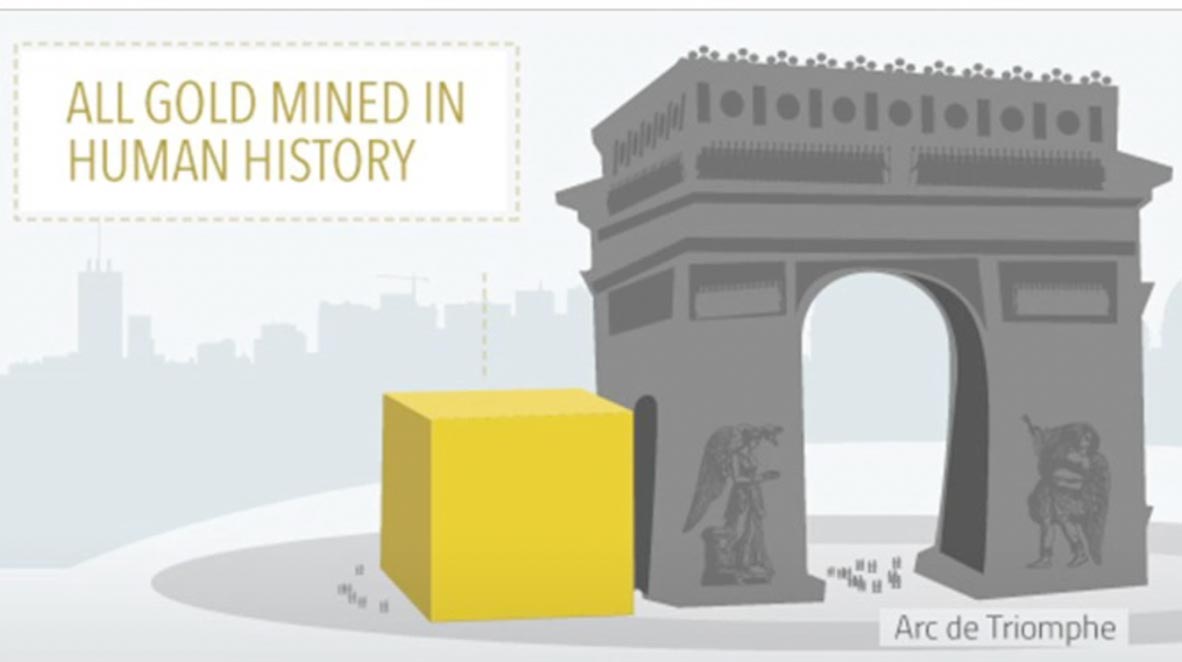

Storied since ancient times, gold and silver were the first metals to be mined because they exist in their natural state. In 2021, according to the World Gold Council, 205,000 tons of gold were extracted, 2/3 of which were during the last 50 years. And the story continues: the mines are growing, becoming more complex, and inventing techniques to dig even deeper because the gold content is constantly decreasing. Today, only between 0.2g and 5g of gold is found per ton of ore. The impact on the environment is increasing exponentially in terms of energy, water and space.

3/ The hidden face of gold: cyanidation

This devastating cyanide-based technique concerns 80% of the gold mined in the world. This particularly effective substance, much more powerful than mercury or chlorine, is mixed with the extracted and crushed ore: it sticks to the gold atoms to form a complex that is recovered in water. Until now, the operation was carried out in storage tanks, but to accelerate the process when the gold content is extremely low, producers set up heap leaching in the 1980s: they make mountains of ore that can reach or even exceed the size of the Eiffel Tower, on which cyanide water percolates… This forms clouds that move with the wind and leach into nature, creating a situation that’s impossible to control.

4/ Tons of embarrassing waste

What to do with the billion tons of ore extracted each year and contaminated by cyanide and other heavy metals? The Grasberg mine in Indonesia, with the consent of the authorities, creates piles of 10 to 20 meters over 200 km2 that it dumps into rivers. On Google Earth, the aerial views of Johannesburg show 6 billion tons covering 400 km2. Next to it, the Soccer City stadium (95,000 people) seems like a tiny speck! The impact on drinking water mean that it now has to be brought from Lesotho, more than 350 km away. And across the world it’s often the case that the dykes of a storage area break – as many as four or five times a year. In 2000 at Baia Mare in Romania, 300,000 m3 of contaminated water spread inland, into the Tisza and the Danube, decimating fauna and flora along the way. The disastrous impacts on nature last so long – in some cases for millennia – that computer projections are no longer able to estimate them.

5/ Can we stop this ecological disaster?

Unlike agriculture or energy, the mining industry is young (200 years) and still benefits from an exceptional status in France and abroad. For Systext, there is no other way than to put an end to cyanidation and to define no-go zones, areas with high ecological value. This would be equivalent to stopping industrial gold mining altogether and switching to recycling, which we know how to do perfectly well. The stocks are largely sufficient to satisfy non-functional needs. Remember that 55% of the primary gold produced today is still destined for the jewelry industry. There’s absolutely no need to perpetuate this ecological disaster!

Banner image © Systext

Related articles:

Patrick Schein, the voice of responsibly mined gold

Cofalit, la “dernière matière” de Boucheron

Mazarin, the new brand from Louise de Rothschild and Keagan Ramsamy