Style

26 February 2020

Share

“Men’s Jewelry, Signs and Insignia”

Despite its long history, little research has been devoted to men’s jewelry. The School of Jewelry Arts explores this glorious subject through the prism of art, cultures and periods of history.

By Sandrine Merle.

The inventory of men’s jewelry, just like that of women, ranges from rings and necklaces to chains and earrings. Down the ages, men have willingly covered themselves with jewels from head to toe, like the sovereigns Henri VIII or Gustav III of Sweden, who perfectly embody the “man in all his finery”, not unlike the peacock spreading its tail. It wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that a radical change of style took place: men shed their jewelry because “the aristocracy gave way to a more discreetly elegant bourgeoisie,” explains Gislain Aucremanne, Professor at the School of Jewelry Arts. It was, you might say, a transition “from peacock to penguin”.

Jewels of power

Among men, jewelry is used to display power, opulence and prestige. In the West, kings wore sumptuous regalia, symbolic objects consisting of crowns, a scepters, or swords decorated with stones, clasps known as the “fermail de Saint-Louis” and sometimes finely wrought gold spurs studded with gems. But it was never enough, it was all about “more and more”. To receive the Persian ambassador, Louis XIV wore a vest entirely covered with diamond buttons: “his clothes were so heavy that the king changed them immediately after dinner,” noted one observer. Maharajas of Patiala, of Kapurthala, the Nabab of Arcot, one of the vassals of the Nizam of Hyderabad… In India, the various princes also rivaled each other in finery, pearl and stone necklaces along with swords, harnesses, belts, buttons and turban ornaments, known as the sarpech.

Rings and regal adornments

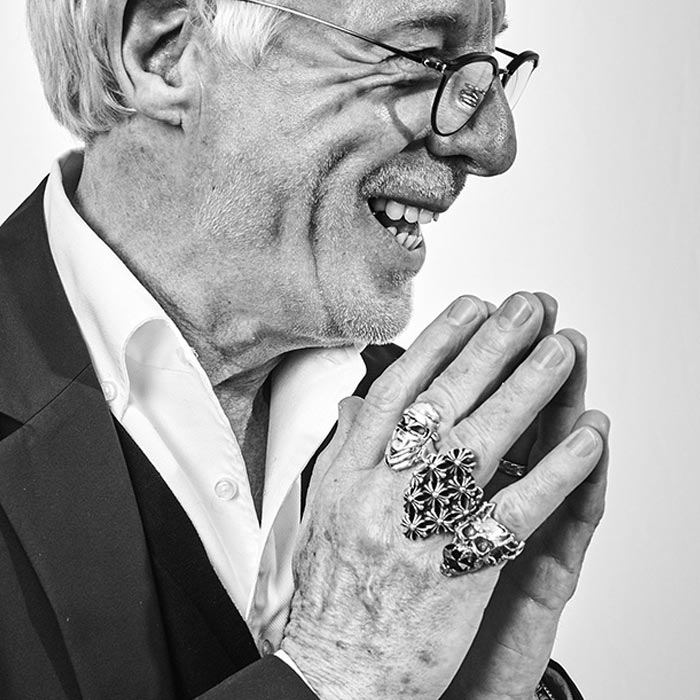

The ring is the regal adornment par excellence. The Doge of Venice, representative of the State, received one in gold, which he threw into the Adriatic when he took office. It was as if he was marrying the city. The hands of priests were also adorned with sumptuous models such as those in the Yves Gastou collection worn by the religious elder of the Dogon tribe in Mali or created by the jeweler Mellerio. “The latter are huge because they were made to be worn over gloves,” says Gislain Aucremanne. They are decorated with crosses and symbols of Christ’s passion and the choice of stones follows very precise codes: for the Pope, a white or colourless stone (rock crystal, diamonds, etc.), for the cardinal dressed in scarlet a red stone and for the bishop clad in purple, an amethyst.

Honorary jewelry, order and the crown

Men’s jewelry celebrates reward, triumph or glory. In ancient Greece, poets and sportsmen were awarded a crown of laurel leaves (an attribute of Apollo) in gold, a bacca laurea, the origin of the word baccalaureate. In 1430, to honour his closest companions, Philippe Le Bon was the first to create an Order, that of the Golden Fleece, recognizable by its necklace, with its alternating gun and fire-stone motifs, and the ram’s body pendant. Louis XI retorted by creating the Order of Saint-Michael, characterized by a necklace of scallops and a medallion representing the archangel slaying the dragon. There was also the Order of the Holy Spirit with a Maltese cross and a dove, worn on a blue ribbon, the Order of the Garter, and the Order of the Legion of Honour created by Bonaparte, which still exists today.

Political jewels, witnesses of history

Men’s jewelry is also a testament to history. At the time of the French Revolution, many creations more or less openly expressed political ideas. The floral rings bearing the royalist motto are unequivocal, as are those bearing the 1792 portraits of the three “martyrs of freedom”: Danton, Marat and Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau. By contrast, a mechanism had to be operated to open the bezel of the commemorative ring representing a tomb: a lock of Louis XVI’s hair was carefully hidden inside it. The seditious jewels fomenting revolt and uprising were not immediately apparent either: only on lifting a fringe of pearls from a pin, created around 1830, can one read VHV, or “Long live Henri V”.

Piercings: infamy and femininity

Piercing has had many meanings down the ages, unlike in the case of women. In the Middle Ages, piercing one’s body was a sign of infamy. On the painting “Christ before Pilate”, the evil characters ones are therefore stigmatized by rings in the cheeks, nose and lips. Worn in the ear, the ring also denotes a foreigner or stranger, such as a Magus, or belonging to a group, whether it be the Grognards (soldiers of Napoleon’s guard) or the Compagnons. The tiny earring of the Compagnons was known as a “stud” and could be adorned with pendants representing a trade. “It is said that sailors and pirates like Corto Maltese pierced their ears to get a better view: in reality, their earring was used to pay for a funeral if they died far from their country,” explains Claudette Joannis, a jewelry specialist. The male earring was also seen as the emblem of a certain femininity worn by Henri III, or more recently in the 80s and 90s.

Canes and signet rings

In the 19th century, the codes of masculine elegance prescribed that jewelry be kepy to a minimum. Oscar Wilde, Honoré de Balzac, Huysmans: dandies, writers, journalists often carried only an ornamented cane and wore a signet ring engraved with their coat of arms. The latter represented filiation in Salic law countries where the title is transmitted by male means. But woe betide anyone who violated these codes! Colette castigated the social columnist Jean Lorrain as follows: “What he was wearing was in poor taste. He was satisfied with cheap jewels or flawed gems, chalcedony or chrysoprase, opal and olivine. Large rings in tortured gold which were hardly fit for display… and which he nevertheless displayed.” In the 20th century, men’s jewelry was still limited to a watch engraved with initials or messages (such as Boucheron’s “Reflection” offered by Edith Piaf to each of her lovers) and a wedding ring. One of the most popular, the Cartier Trinity with 3 rings became famous thanks to Cocteau who is said to have given it to his friend Radiguet.

Signs of rebellion

Men’s jewelry is also synonymous with punk, grunge, etc. counter-cultures. Astride their huge machines, Hell’s Angels in leather jackets and tattoos swear by the chains and outsize rings depicting funeral angels, bat wings or skulls that serve as their emblems. The latter turn into genuine weapons when they are spiked or contain a full set of bunched fingers like American punches. All these jewels were later misappropriated by rockers, especially those depicting a skull, a memento mori reminding us of how life must end. Keith Richards’ famous silver ring is modelled precisely on the shape of his own skull.

Today, fashion shows as well as the success of certain bracelets such as Fred’s Force10 show that men are getting back into jewelry. There’s no such thing as shamein this brave new (men’s) world.

Banner image : Rings from 70s © Yves Gastou collection – Albin Michel, picture: Benjamin Chelly

Related articles: