Style

09 December 2019

Share

Precious Art Deco materials

Precious materials such as jade, diamonds, lacquer, exotic woods and sharkskin, from equally exotic places, infused Art Deco creations in the 1920s and 1930s. And not only in jewelry…

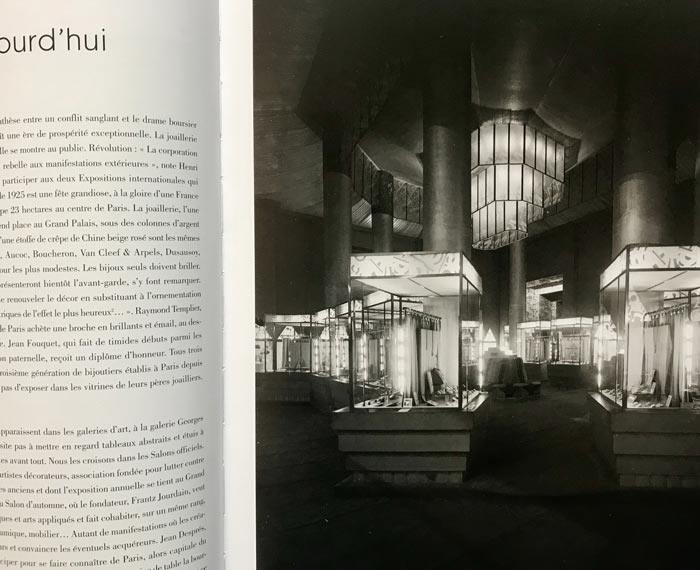

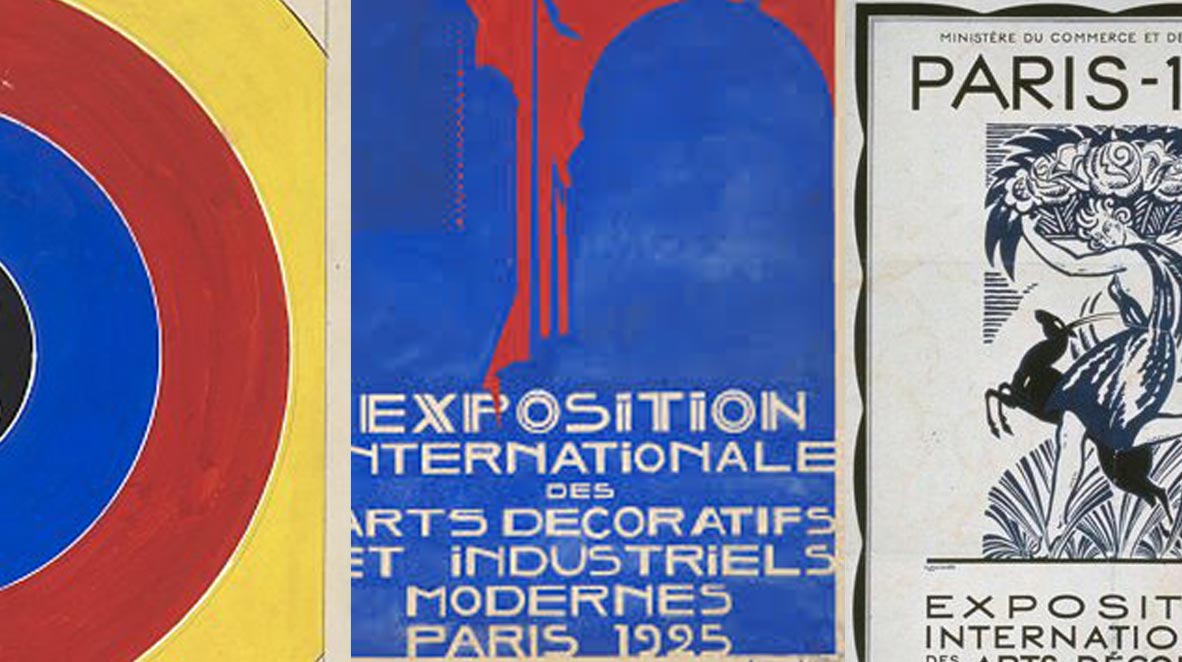

The Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, which people had dreamed of for an entire decade, served to revive the cultural power of France, and a taste for the arts, shortly after the end of the First World War. The mission proved a ringing success: between April and October 1925, the 1,000 exhibitors attracted almost 6 million visitors. The impact was global. It later gave its name to a style: Art Deco, which would continue to flourish until the Second World War. In retrospect, this style – a rejection of the excesses of Art Nouveau – consisted largely of geometric and symmetrical lines, in bright and clear colours. But it was much more complex than that, and drew on multiple influences, complete with surprising references to the 18th century in France and to distant civilizations. In a colonial France, Art Deco demonstrated a predilection for the rest of the world: Egypt, India, China and Japan. A look back at this extraordinary phenomenon.

Starting with the French Embassy pavilion…

Art Deco gave pride of place to collaborative work. In the Embassy Pavilion, André Groult, Marie Laurencin and Pierre Chareau worked together under the direction of a designer: in this case the great Jean Dunand, an emblematic figure of Art Deco. In so doing, they showcased rare and therefore precious materials. André Groult’s chiffonnier (a tall piece of furniture with drawers in which ladies stored their accessories), with its curved shapes, draws attention to the skin-coloured sharkskin. It borders on the indecent… You can feel the breasts, the stomach, the hips. “This very fashionable material takes its name from Jean-Claude Galuchat, an 18th century sheather, working on the Quai de l’Horloge. It is made of shark and ray skins caught in the South Seas and then tanned,” says Béatrice Vingtrinier, art historian and Professor at the School of Jewelry Arts. Very popular with designers like Paul Iribe, sharkskin would end up a virtually forgotten material. Too hard to work with, too luxurious!

… and then moving on to the Hôtel du Collectionneur.

Several artists worked in this residence of an imaginary collector, including Bourdelle on the sculptures, François Décorchemont on the fabulous glass chandelier and Puiforcat on the metal work. In the boudoir, the preciousness of the marquetry highlights the palm wood from Gabon worked with mahogany, and the ebony of Macassar from Indonesia inlaid with ivory. Ivory alone symbolizes one of the major influences of Art Deco: Africa. Jazz was the height of fashion, coinciding with the Harlem renaissance. Picasso discovered this civilization thanks to his friend André Derain, a great collector of masks from Gabon. One of the most fervent ambassadors was the very rich heiress, Nancy Cunart, who published an anthology of 150 African-American authors. In the well-known portraits of Man Ray, she is graced by her ivory necklaces, her arms covered by a collection of wooden bracelets.

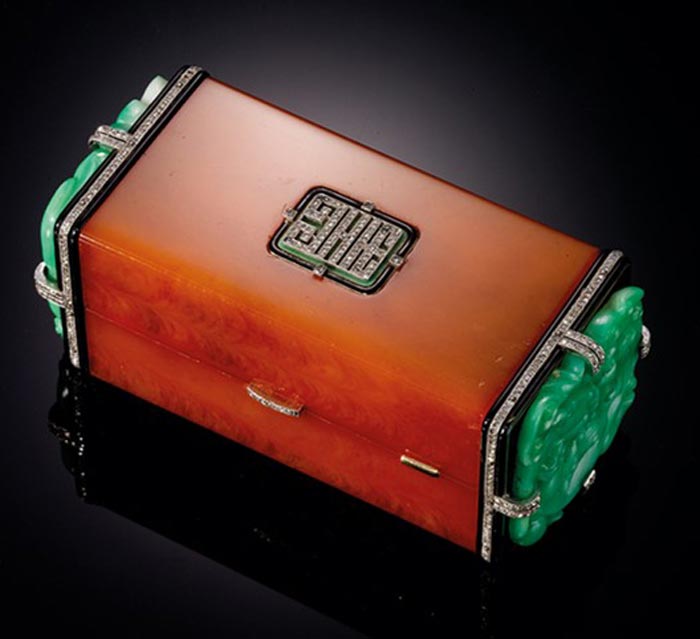

Exchanges and collaborations

In this imaginary collector’s home, we discover Jean Dunand’s lacquered furniture. Lacquer (also used for the orange-red spots on her “Giraffe” necklace) was one of the most emblematic materials of the time. It came from Japan: “Jean Dunand trained with a very famous lacquerer, Seizo Sugarawa, as did the decorator Eileen Grey before him. This technique requires a great deal of patience, it’s a painstaking task, superimposing layers that have to dry for hours,” explains Céline Gaslain-Leduc, PhD in art history and Professor at the the School of Jewelry Arts. For their boxes, cigarette cases and other compacts, Lacloche jewelers made extensive use of this material, which can also be inlaid with mother-of-pearl or egg shell.

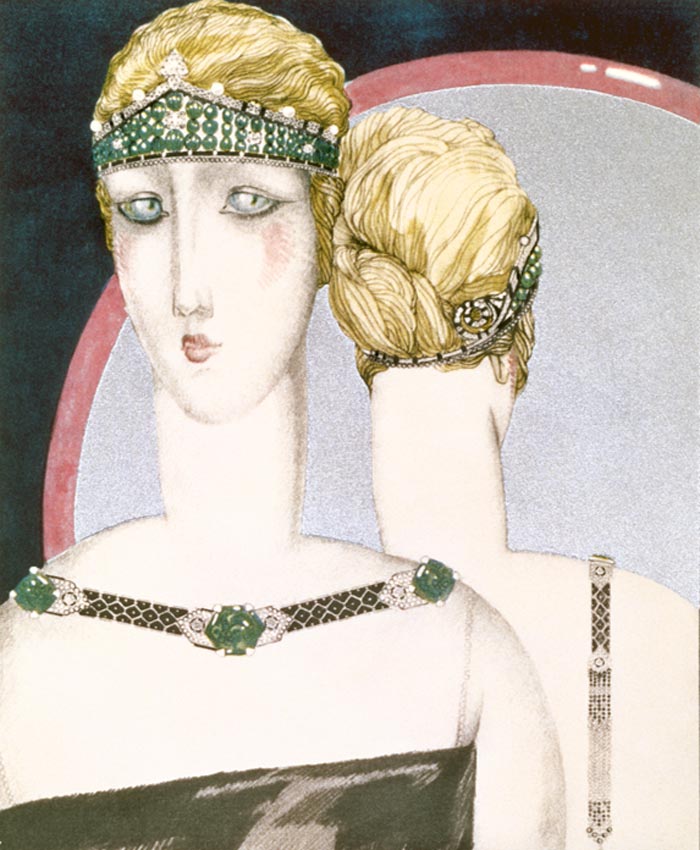

In the Pavilion of Elegance

Here, we may admire the work of couturiers like Worth (the first to brand his dresses with his own name), the Callot Sisters, and especially Jeanne Lanvin. The latter excelled in the jewelry dresses typical of the roaring 1920s: straight, sleeveless and barely covering the knee. They were cut from new, very fine and fluid fabrics embroidered with glass beads, silver or gold tubes. They are used as jewelry because there was no question of hanging a brooch on them: that would certainly damage them! New jewels appeared, such as bracelets worn in accumulations or long necklaces, which trembled and shimmered at the slightest movement. A few steps away, the “Bérénice” piece presented by Cartier is perfectly wrought: this shoulder jewel, with no attachment, drapes itself on the neckline and falls back into the back. The central engraved emerald of 141 carats, brought back from Colombia by the Conquistadors, was, once again, shot through with an exotic touch.

The jewelers

The thirty or so French jewelers who took part in the Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts concocted a veritable fireworks display of precious materials! Take, for example, the jade work, polished rock crystal on earrings by Suzanne Belperron, creator of the René Boivin house. At this exhibition, Mauboussin earned a gold medal thanks to his work with ideas of fullness and emptiness on the platinum and baguette-cut diamond tiara (the new fashionable cut) – amongst other pieces. At Van Cleef & Arpels, diamonds were combined with rubies, onyx and emeralds featuring Egyptian figures inspired by the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. The latter also created new colour blends based on carnelian, turquoise and lapis lazuli – a complete break with traditional codes of accepted good taste!

A flood of colored gemstones

Three years after this 1925 exhibition, the Maharajas, heirs of the Mughal emperors, arrived in Paris with their chests overflowing with coloured precious stones: sapphires, rubies, engraved emeralds, pearls… They all wanted to bring them up to European standards, i.e. on platinum and clawed settings. Conversely, French jewelers drew inspiration from their techniques such as kundan, a technique of encrusting stone in gold, jade and rock crystal using gold leaves folded over themselves and amalgamated to form a closed seam. Cartier recycled elements of Indian jewelry in contemporary frames: a bazuband (traditional arm bracelet) thus became a brooch.

Almost a century later, the influence of Art Deco persists in jewelry collections. The contemporary designer Viren Bhagat has even invented an “Indian déco” style, in which he injects elements of Indian jewelry such as “mirror” stones, i. e. flat stones or the figure of the peacock. Simply eternal.

More “Evening Conversations” at the School of Jewelry Arts: