Business

23 March 2016

Share

The “ladies’ workshop” at René Boivin

René Boivin: in fact, behind the name of this prized French jeweler hid a team of women.

By Sandrine Merle.

The vast majority of the pieces produced by the René Boivin workshops were not designed by the founder, who died in 1917 of pleurisy, but by ladies working for the company. This is why Françoise Cailles, author of the only book (to date) on the brand, describes it as the “ladies’ workshop”.

Jeanne Boivin, his wife

After the First World War, Jeanne Boivin (sister of the fashion designer Paul Poiret) changed course, steering René Boivin – until then a manufacturer for major brands – in a more creative direction. “She had quite a character”, explains Olivier Baroin, Suzanne Belperron’s expert who worked with her for 13 years. At that time, jewelry was primarily a man’s world. “Jeanne Boivin signed all her letters as ‘René Boivin Esq’ until the 1960s,” he explains. She supervised everything with extreme care. In 1919, she hired the young Suzanne Vuillerne (known under the name of her husband Belperron), and the duo worked in close collaboration until Belperron was appointed co-director in 1924.

Suzanne Belperron

Belperron played a key role in the history of René Boivin. The designer introduced new contrasts of wood and diamonds, rock crystal and colored gemstones such as amethysts, sapphires, peridots, etc. She favored the highly fashionable yellow gold with platinum, and the use of architectural volumes. In thirteen years, she created the Boivin style: the jewels have a definite look – identifiable at first glance. “When she was away, customers would drop off gold and stones and say, ‘Tell Madame Belperron to do whatever she wants!'” says Olivier Baroin. However, Belperron left the company in 1932 although we don’t know why or under what conditions. Even her own archives shed no light on the matter.

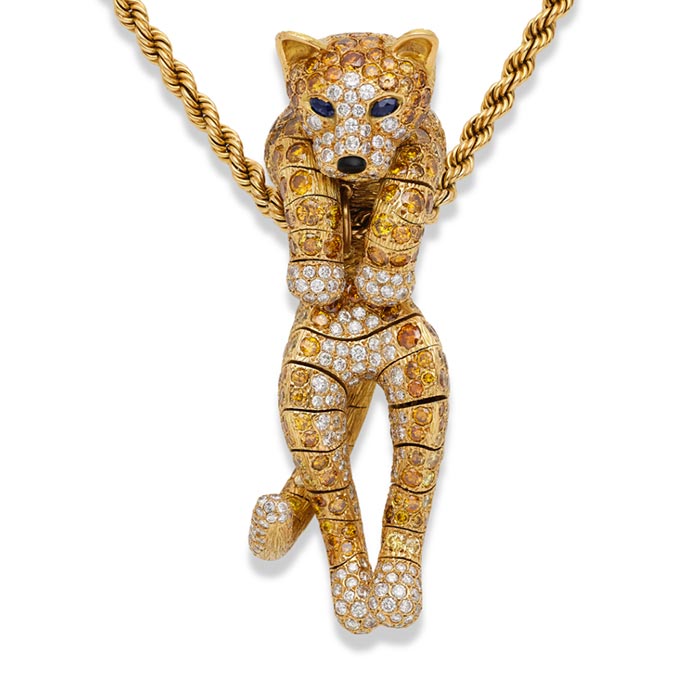

Juliette Moutard

In 1933, Juliette Moutard succeeded Suzanne Belperron. She was humorous and spirited, as can be seen for example in the mischievous touches of her bestiary. She was a bird lover, very much in tune with the ideas of Jeanne Boivin, who adored the marine world – in particular starfish and their articulated fingers. One of the most famous pieces from 1937 was the five-fingered variety designed in 1936 for the actress Claudette Colbert. At the same time, she upheld the tradition of the brand’s beloved architectural forms and Etruscan influences. “She probably got along better with Madame Boivin than Suzanne Belperron, since she stayed with the company for almost 40 years,” says Olivier Baroin. Before her retirement in 1970, she was assisted for a few months by a new designer: Marie-Caroline de Brosses.

Marie-Caroline de Brosses

When she arrived in 1970, Marie-Caroline de Brosses (who has since passed) first worked under the direction of Jeanne Boivin’s daughters, Suzanne Voirin and Germaine Sonrel, and then from 1975, under Jacques Bernard. The two sisters sold the house to their supplier of colored diamonds, Mr. Perrier, whose daughter, Françoise, was married at the time to Jacques Bernard (a former Cartier workshop manager). In 1982, Mme Perrier inherited René Boivin, which she sold to her ex-husband in 1989. Over the years, Marie-Caroline de Brosses reprised the brand’s emblematic motifs: Paisley, scrolls and scales imbued with the spirit of the the 1980s. She designed Jean d’Ormesson’s ceremonial sword on his admission to the Académie Française. She left René Boivin in 1989 shortly before Jacques Bernard sold the brand in 1991 to Asprey (then owned by the Sultan of Brunei’s brother).

Marie-Christine de Lamaze

From 1974, Marie-Caroline de Brosses spent a large part of her time abroad, in Korea. To assist her in Paris, she called on one of her former classmates from the Beaux-Arts: Marie-Christine de Lamaze. They worked completely independently but it’s often difficult to tell their work apart. She created pieces for prestigious and famous clients such as Marina Vlady and the Faisal princesses, and also designed a sword for Maurice Rheims.

Ghislaine d’Entremont

In 1985, Marie-Caroline de Brosses called upon another of her fellow Beaux-Arts graduates: Ghislaine d’Entremont. D’Entremont was a highly original artist, whose creative works strictly upheld the traditions of the brand. She had a passion for stones and knew how to maintain excellent commercial relations, which kept the company’s prestigious clientele loyal. In 1988, she gave up her position to Sylvie Vilein and went to work for Chaumet and then for Chanel.

Sylvie Vilein

In 1988, Jacques Bernard hired Sylvie Vilein. A graduate of the Haute École de Joaillerie, she also took drawing classes which helped her to enter into productive relationships with the people in the workshop, and to share the same language and creative vocabulary. A perfectionist with a brush, she created the last spectacular and articulated jewelry, such as the octopus – one of the brand’s hallmarks – a distant echo of Juliette Moutard’s earlier starfish. From 1999, she continued her career at Poiray and then, since 2004, at Mauboussin.

Until the end of the 90’s, therefore, it’s clear that the René Boivin style was kept alive by a series of prominent ladies – in a sector entirely dominated by men.

Related articles:

Thomas Torroni-Level and the Boivin archives

Olivier Baroin, the expert of Suzanne Belperron